Weapon of Mass Doubt: Were the U.S. Atomic Bombs Deployed Over Hiroshima and Nagasaki Truly Atomic?

- Kejsi Kajo

- Aug 22, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Oct 12, 2025

The use of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945 remains the only instance in which nuclear weapons of any kind have been used in armed conflict.

The uranium-based bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Little Boy, killed roughly 70,000 people instantly, while the plutonium-based bomb dropped on Nagasaki three days later, Fat Man, instantly killed roughly 40,000 people. By the end of the year, the nuclear attacks had caused over 30,000 additional deaths in each city.

Less than four months into his first presidency, President Harry S. Truman authorized the deployment of the unprecedented weapons in an effort to bring an end to World War II and save countless American lives by avoiding a prolonged invasion of Japan.

According to a 1984 Financial Times article, The Legacy of Harry Truman: Enduring mark of a 'great little man', President Truman, who had been completely uninformed about the U.S. atomic advancements while Vice President, was made aware of the nuclear weapons "at the end of his very first cabinet meeting".

English journalist and historian Godfrey Hodgson wrote that President Truman, "had no difficulty in deciding to order the dropping of two atom bombs on military targets, but in crowded cities, after an ultimatum and without any harmless demonstration of the new weapon's destructive power".

The late author, who extensively studied and covered American politics, believed that the destruction of Hiroshima "was an irreparable act, one which for ever deprived the American people of a certain claim to historical innocence", but it could "perhaps be justified" on the grounds that "a successful conquest of Japan by conventional means would take a year and cost half a million American and countless Japanese lives".

"It is hard to defend the bombing of Nagasaki", Hodgson comments. A 1975 excerpt in The New York Times likewise questioned, "After Hiroshima, was Nagasaki necessary?". The brief text asserts that the reasons for the destruction of Nagasaki "have been more difficult to reconstruct than the city itself".

The former mayor of Nagasaki, Hitoshi Motoshima, stated that "the atomic bombings were one of the two greatest crimes against humanity in the 20th Century, along with the Holocaust", documented in a 1995 International Herald Tribune article titled "Japan Ignites A Firestorm Over Use of Atom Bombs", written by American author Paul Blustein. Motoshima "apologized for Japan's own war misdeeds", reflecting on the Pearl Harbour attack, which prompted the United States to enter World War II.

The city's former leader dismissed the claim that "the bombings were necessary to bring World War II to a speedy end" and argued that "the United States was motivated to drop the bomb in part by the $2 billion that the weapon cost to develop", in reference to the Manhattan Project, a classified government-funded research program that pursued the development of atomic weapons before Nazi Germany could.

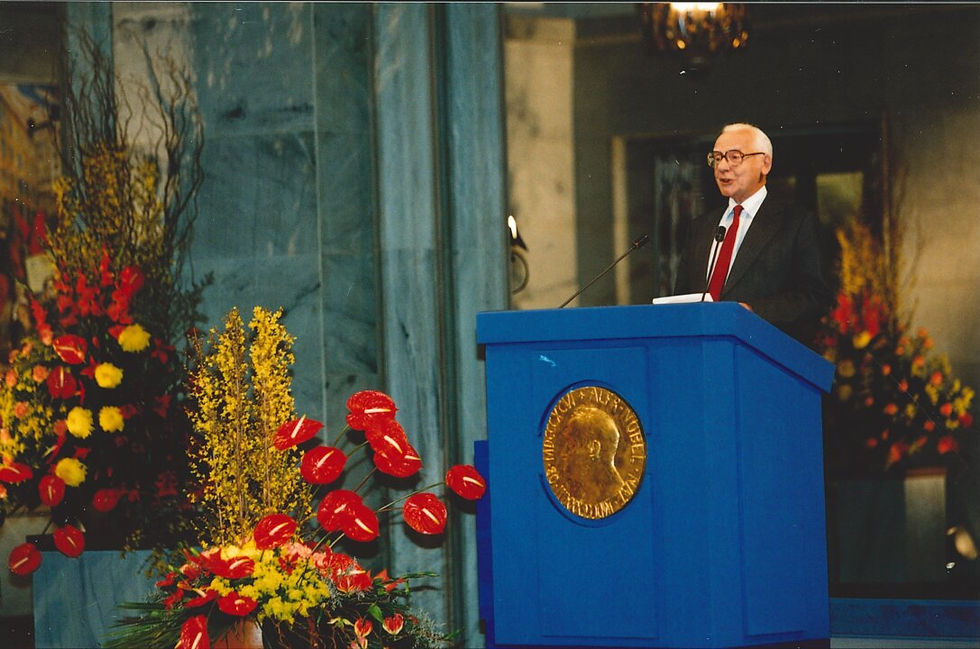

A Polish-born atomic scientist, Dr. Joseph Rotblat, who worked in the U.S. nuclear program in Los Alamos, New Mexico, withdrew from the Manhattan Project in 1944 "because he had concluded that the bomb would be used to intimidate the Soviet Union, rather than deter Germany", reported in a 1995 Financial Times article titled "Atomic scientist wins peace prize".

"I realized that the Hitlerites would not be able to develop an atomic bomb", said the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize awardee. When the Japanese cities came under nuclear attack, Dr. Rotblat's "horror deepened". He had regarded the nuclear weapons as "a never-to-be-used deterrent aimed at forcing Nazi Germany to drop its own nuclear plans".

The acclaimed atomic scientist "was spurred to protest against the nuclear arms race by the pangs of conscience he felt over playing a part in producing deadly weapons".

The former mayor of Hiroshima, Takashi Hiraoka, who "also questioned US motives" for resorting to nuclear force, maintained that the use of atomic weapons in Japan was a result of "Washington's desire to demonstrate its military power and block Soviet expansion in the Far East".

Blustein wrote that Japanese officials had condemned the nuclear strikes for decades, but they had not accused the U.S. of "violating international law or morality" because of the Tokyo-Washington alliance and "the national sense that a defeated country should accept its fate". The former mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki further established that "their main purpose was to achieve total nuclear disarmament, not to point fingers".

The United States continued nuclear research under strict secrecy following World War II. According to a 1993 Financial Times article titled "US reveals 200 secret nuclear tests", the secretary of energy under President Bill Clinton, Hazel O'Leary, stated that the U.S. "had conducted 925 nuclear tests between 1945 and 1990, including 204 previously undisclosed".

"We were shrouded and clouded in an atmosphere of secrecy. And I would even take a step further - I would call it repression", O'Leary said in an announcement. She revealed that the U.S. "had used 98 tons of plutonium in weapons production between 1945 and 1988" and that the "plutonium inventories at US nuclear weapons production sites now totalled 33.5 tons".

The U.S. government had admitted that some of the "secret tests accidentally sent small quantities of radioactive gas into the atmosphere".

A 1999 The Independent article, "Deadly legacy of Hiroshima in US", addressed a surge of health concerns associated with radioactive exposure near the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, which was opened in 1944 and "produced the plutonium for the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs under conditions of the utmost secrecy".

The author of the article, journalist Andrew Gumbel, wrote that ever since, "billions of gallons of radioactive liquids and billions of cubic metres of radioactive gases had been released into the surrounding area". The release of the radioactive materials "ravaged the health of the local population, poisoned the air and the soil, infected the local livestock and contaminated the nearby Columbia river".

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle "spent 10 years and $18m" investigating the increase of "the unusually high incidence of thyroid disease in the Hanford region" and "miraculously" concluded that "the nuclear plant and its toxic emissions are not responsible for it". An environmental researcher, Tim Connor, described the study as "statistical wizardry".

Trisha Pritikin, who "grew up in the shadow of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, the weapons plant in the wilderness of eastern Washington state", said that the study "does a complete disservice to people ... who have seen families members fall ill and die".

"About two million people have been exposed to radioactive iodine, which is absorbed by the human body through the thyroid gland can cause hormone deficiencies and cancer", Gumbel stated.

A 1980 The Times article titled "A glimmer of hope in the nuclear threat" reported on the intergenerational health consequences of atomic radiation on Hiroshima survivors. Medical Correspondent Dr. Tony Smith wrote that "nuclear radiation is known to induce cancers, and especially leukemia", but "in absolute number the mortality from leukemia has not been overwhelming" among Hiroshima citizens who were "exposed to intense radiation".

Dr. Smith noted that the local population who suffered the nuclear attack "had no nuclear shelters; nor did they use their conventional shelters, for the all-clear was sounded at Hiroshima some minutes before the atomic bomb was dropped from a sunlit sky".

The former deputy editor of the British Medical Journal asserted that the new generation of Hiroshima citizens, "whose parents were irradiated but survived" the historical atomic bombing, did not demonstrate any evidence of "altered chromosomes or any increase in congenital deformities".

"Hiroshima: Where hell reigned, flowers bloom", a 1985 The Jerusalem Post article similarly reported that "In recent years virtually no survivors have displayed new symptoms of radiation after-effects".

The article states that "Forty years after it was devastated in the world's first nuclear attack, Hiroshima has blossomed out of ruin and radiation into a thriving city ten times its former size". Many people "believed vegetation could never grow again", but "today lovingly tended trees, shrubs and flowers flourish everywhere along broad avenues".

Michael Palmer, an American author and physician who believed that "mainstream history is not always truthful", challenged the atomic nature of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki strikes in his book "Hiroshima Revisited: The evidence that napalm and mustard gas helped fake the atomic bombings".

Palmer suggested that the United States deployed a "dirty bomb" in Japan, which combined radioactive materials with "poison gas, napalm, and high explosives". The alleged poison gas, sulfur mustard, "mimics both the acute and the chronic effects of radiation on the human body". He stated that the U.S. "had stockpiled sulfur mustard in World War II and had even conducted experiments on some of their own soldiers".

The author mentioned the personal account of a Russian-American aviation pioneer and inventor, Alexander P. de Seversky, who was sent on "an official mission to report on the results of the Allied bombing campaigns in Germany and Japan". The destroyed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki "had impressed him in much the same way as the many cities destroyed by conventional air bombing which he had visited before".

De Seversky published a non-fiction book in 1950, Air Power: Key to Survival, where he shared his impression of the nuclear aftermath in the Japanese cities. The military strategist described a "lack of evidence" of the nuclear weapons' "distinct and apocalyptic effects". He wrote,

"I had heard about buildings instantly consumed by unprecedented heat. Yet here were buildings structurally intact, with outside and stone facings in place. What is more, I found them topped by undamaged flag poles, lightning rods, painted railings, air-raid sirens, and other fragile objects".

Palmer further questioned the trail of the "missing uranium": The Hiroshima atomic bomb contained 64 kg of total uranium, of which less than 1 kg went through the reaction that caused the explosion. The author wrote that "Several scientific studies have looked for this uranium, but all have come up short". He noted that the U.S. military did not show as much interest in "the intensity of the radiation produced" as to the "strength of the explosion".

The nuclear detonation over Hiroshima generated the infamous mushroom cloud. Palmer highlighted a New York Times article titled "The Hiroshima Mushroom Cloud That Wasn't", which "claimed that the mushroom cloud above Hiroshima was caused by the burning of the city rather than the nuclear detonation".

A 1948 report in The Journal of the Florida Medical Association, "Effects Resulting from Atomic Bomb Explosion", claimed that "some fires close to the center of the explosion were undoubtedly started by the radiation of heat", but the majority of the massive fires consuming the Japanese cities following the destructive attacks "were of secondary origin, starting from electrical short circuits, broken gas lines, stoves and like sources".

Medical professional Frank L. Price wrote, "In Hiroshima, 60 per cent of those who died immediately, and in Nagasaki, 95 per cent of those who died immediately, did so from burns". The survivors' predominantly second-degree burns "were limited to that part of the body facing the center of the explosion. Clothing of any sort gave protection".

Dr. Price stated that gamma radiation and neutron exposure accounted for approximately 7 percent of the immediate deaths.

The medical expert concluded his report with a comment on the psychological toll that the atomic bombings inflicted on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

"One of the most significant effects of the atomic bomb was the sheer terror which it struck into the people of these bombed cities. Persons who had become accustomed to mass air raids had grown to pay little heed to single planes or small groups of planes, but after the atomic bombings, the appearance of a single plane caused more terror and disruption of normal life than the appearance of many hundreds of planes had ever been able to cause before".