U.S. vs IBM: The Longest Case in U.S. History Meets "The Crankiest Judge in America"

- Kejsi Kajo

- Sep 6, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 19, 2025

The 13-year-old anti-trust lawsuit brought by the Department of Justice against the multinational technology company International Business Machines Corporation in January of 1969 remains one of the longest and most significant legal cases ever filed in U.S. history.

The DOJ accused the defendant of monopolizing, or attempting to monopolize, the general-purpose computing market through a series of anti-competitive practices. IBM, which accounted for around 70% of the market’s share, argued that its conduct nurtured competition and lacked monopolistic intent.

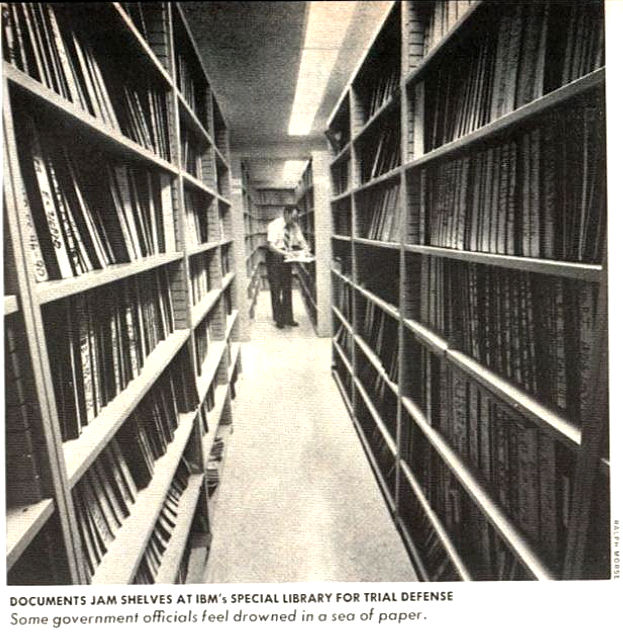

The lawsuit, brought before the Southern District of New York, generated roughly 30 million documents and thousands of hours of testimony from over 900 witnesses. One of the nine U.S. attorneys general who oversaw U.S. vs IBM, Griffin Bell, said that "the duration of the IBM case suggested there might be something wrong with the US court system", documented in a 1979 Computer Weekly Supplement article titled "'Settle 10-year-old IBM case,' says ex-law chief".

According to American author Paul Hoffman's journalistic exposé "Lions of the Eighties: The Inside Story of the Powerhouse Law Firms", the Second Circuit Court of Appeals asserted that "no litigation [had] taken so much time and involved so much expense".

Hoffman wrote that the litigating parties "could not even agree on the parameters of the case or the measurements to determine them". The U.S. government recognized only three rivals to the defendant, "while IBM claimed ninety".

The plaintiff excluded telephone companies from the competitive landscape surrounding IBM’s market dominance, even though in a prior lawsuit filed by the U.S. government against AT&T, "the government charged AT&T with excluding IBM as a supplier so that it could purchase its own, inferior equipment".

A 1977 Time article titled "Those Cases That Go On and On" described the lawsuit as "a fight over information — the Government asking for vast amounts, the company often resisting". Former U.S Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, "IBM vice president in charge of the legal defense", stated, “Sometimes plaintiffs ask for something we don’t have—we'd have to ask every salesman in every branch office—because it’s not the sort of information that the company needs to run itself".

"Or sometimes they ask for a file from the early ‘60s, and those files are crated up in the warehouse with empty Coke bottles and dead mice", he added.

Hoffman wrote that the former district judge for the Southern District of New York, David Norton Edelstein, who presided over the anti-trust lawsuit for its entire duration, operated under the "kitchen sink theory", "allowing virtually everything to go into the record, with his ruling later on its relevance".

Judge Edelstein supposedly said to a witness, "Take your time. I'm ready to go every single day — today, tomorrow, Monday, all the way through Tuesday — till midnight or till we drop with exhaustion".

A 1973 International Herald Tribune article, "IBM Ordered To Pay Daily $150,000 Fine", reported that the relationship between IBM and the judge was "severely strained". Edelstein had recently "found IBM in civil contempt of court for refusing to deliver a batch of corporate documents to the Justice Department".

The Justice Department made a plea to impose "a large daily fine" on the defendant, which the judge accepted. Edelstein ordered IBM to pay "$150,000 for each day that it failed to turn over the disputed documents". IBM attorneys said that "the matter warranted only a token fine of perhaps $100 a day".

"What a Difference a Judge Makes", a 1982 Fortune article, suggested that Edelstein had "something of an obsession about IBM". IBM witnesses shared that Edelstein "had harassed them by shouting, refusing to let them answer, and glowering". One of the witnesses said, "At no time in my life have I felt so abused and demeaned as I did before Judge Edelstein".

Hoffman noted that the judge had called all the expert witnesses "hired guns", who would "testify in favor of whichever side paid them". Edelstein "indicated he put little credence in their evidence".

The discontinued Spy magazine wrote a 1987 article on Edelstein titled "The Crankiest Judge in America", where it reported that IBM turned to the Second Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court three times "in efforts to force Edelstein to recuse himself".

The billion-dollar company filed a 2,000-page motion to reassign the case to a different judge in 1979, where it stated that Edelstein "had sustained objections by the government 60 percent of the time and by IBM less than 3 percent of the time". The appeals court "did not find Edelstein's behavior prejudicial".

According to "'Settle 10-year-old IBM case,' says ex-law chief", "government lawyers" asserted that IBM's accusations against Edelstein "did not satisfy the statutory requirements for the withdrawal of the judge". The "lawyers from the anti-trust division" believed that "IBM had failed to demonstrate Judge Edelstein's stewardship of the case had been tainted by prejudice or bias".

However, a 1975 The Times article titled "Court decides judge erred in IBM ruling" documented that the Federal Court of Appeals agreed that Edelstein had "made mistakes in his handling of the case". The court ordered him to "reverse his ruling on three matters which IBM had opposed".

Edelstein was barred from "refusing to allow IBM lawyers to interview government witnesses unless a Justice Department lawyer is present" and "refusing to hear all motions during the trial". The circuit court overturned one of the judge's court orders, "which directed IBM to file all its papers with his office, rather than allow the documents to be lodged with the clerk of the court".

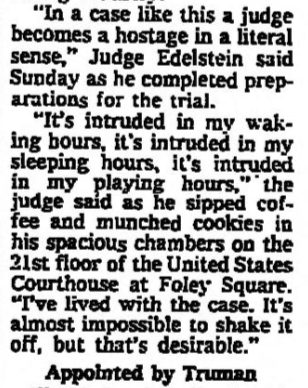

In a 1975 The New York Times article titled "Judge as a 'Hostage'", legal commentator Tom Goldstein stated that U.S vs IBM, litigated in "the largest, busiest and probably most important Federal bench in the country", was "the most significant case of [Edelstein's] career".

Goldstein reported that the district court judge was assigned the anti-trust lawsuit a year after President Harry S. Truman appointed him to the bench. Prior to his judgeship, Edelstein was a Justice Department lawyer. He joined the DOJ in 1944 and served "as a liaison with Senator Truman's committee investigating war contracts".

The New York City Bar, the New York State Bar, and the American Bar Association opposed Edelstein's nomination. Goldstein wrote that "The bar groups contended he lacked sufficient legal experience for the judgeship".

"The Crankiest Judge in America" stated that a New York City Bar representative informed the Senate Judiciary Committee that Edelstein "had a mediocre record at Fordham Law School" and "had failed the state bar exam three times". "Nonetheless, Edelstein was confirmed", the article concluded.

New York litigators, who are "accustomed to being doubted", believed the judge was "progovernment in criminal trials, erratic in civil trials and anti-lawyer all the time". His wrath was allegedly so terrible "that lawyers [found] themselves defending not their clients but themselves". A "former judicial colleague" of Edelstein speculated, "as others have", that "the judge is belligerent because he feels 'insecure and out of his depth'".

One of the lawyers, "known for his humility", said, "I tried to lick Edelstein's boots. He kicked me".

When the Department of Justice voluntarily dismissed the anti-trust lawsuit against IBM in January of 1982, "only four months before the case was to be submitted to Judge Edelstein for a ruling", the judge "was furious". He felt he was denied of his "moment in history".

The lawsuit lost its relevance as the general-purpose computing industry progressively evolved and IBM gradually lost much of its former dominance. Some analysts insist that the 13-year-long legal dispute diminished the company's leading position in the technology sector.

As of today, IBM no longer manufactures personal computers. The digital innovator has become a driving force in artificial intelligence, cloud services, and cybersecurity.

The Red Pen Incident

🗒 March 3rd, 1977

⚲ Federal Courtroom in Manhattan

The "lead counsel for IBM", Thomas D. Barr, one of “America’s most prominent litigators”, “jabbed his red felt-tip pen in the air to drive home a point”. Judge Edelstein “went a little haywire”:

Barr: Your Honor, you should understand this, I have a—

Edelstein: Now, look, don't you point any finger or any pen at me! Now, you just behave yourself. What you need is a lesson in good manners. Now, stop it.

Barr: Your Honor, I am sorry for—

Edelstein: I think you have had too many indulgences, and you have been a very spoiled brat. Now, stop it! Don’t you ever point a finger at me again. Now, you did! And this is not the first time that this has occurred.

Barr: Your Honor, I was not pointing my finger at the court. I was trying to emphasize—

Edelstein: It was in my direction.

Barr: I was simply, with my hand—

Edelstein: I consider that threatening and bullying, and stop it.

Barr: Your Honor, I happened to have the pen in my hand. I would not, under any circumstances, address anything approaching a threat to—

Edelstein: l am not myopic— I am not shortsighted! My vision is reasonably good, and it was in my direction, and that is a finding of fact.

Many lawyers who had appeared before the judge "often cite the Red Pen Incident to bolster their claims that the 77-year-old Edelstein is dangerous, evil—a madman!".

-"The Crankiest Judge in America", Spy Magazine, June 1987